by Joche Ojeda | Feb 7, 2025 | Uncategorized

I recently had the privilege of conducting a training session in Cairo, Egypt, focusing on modern application development approaches. The session covered two key areas that are transforming how we build business applications: application frameworks and AI integration.

Streamlining Development with Application Frameworks

One of the highlights was demonstrating DevExpress’s eXpressApp Framework (XAF). The students were particularly impressed by how quickly we could build fully-functional Line of Business (LOB) applications. XAF’s approach eliminates much of the repetitive coding typically associated with business application development:

- Automatic CRUD operations

- Built-in security system

- Consistent UI across different platforms

- Rapid prototyping capabilities

Seamless Integration: XAF Meets Microsoft Semantic Kernel

What made this training unique was demonstrating how XAF’s capabilities extend into AI territory. We built the entire AI interface using XAF itself, showcasing how a traditional LOB framework can seamlessly incorporate advanced AI features. The audience, coming primarily from JavaScript backgrounds with Angular and React experience, was particularly impressed by how this approach simplified the integration of AI into business applications.

During the demonstrations, we explored practical implementations using Microsoft Semantic Kernel. The students were fascinated by practical demonstrations of:

- Natural language processing for document analysis

- Automated content generation for business documentation

- Intelligent decision support systems

- Context-aware data processing

Student Engagement and Outcomes

The response from the students, most of whom came from JavaScript development backgrounds, was overwhelmingly positive. As experienced frontend developers using Angular and React, they were initially skeptical about a different approach to application development. However, their enthusiasm peaked when they saw how these technologies could solve real business challenges they face daily. The combination of XAF’s rapid development capabilities and Semantic Kernel’s AI features, all integrated into a cohesive development experience, opened their eyes to new possibilities in application development.

Looking Forward

This training session in Cairo demonstrated the growing appetite for modern development approaches in the region. The intersection of efficient application frameworks and AI capabilities is proving to be a powerful combination for next-generation business applications.

And last, but not least, some pictures )))

by Joche Ojeda | Jan 21, 2025 | Uncategorized

During my recent AI research break, I found myself taking a walk down memory lane, reflecting on my early career in data analysis and ETL operations. This journey brought me back to an interesting aspect of software development that has evolved significantly over the years: the management of shared libraries.

The VB6 Era: COM Components and DLL Hell

My journey began with Visual Basic 6, where shared libraries were managed through COM components. The concept seemed straightforward: store shared DLLs in the Windows System directory (typically C:\Windows\System32) and register them using regsvr32.exe. The Windows Registry kept track of these components under HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT.

However, this system had a significant flaw that we now famously know as “DLL Hell.” Let me share a practical example: Imagine you have two systems, A and B, both using Crystal Reports 7. If you uninstall either system, the other would break because the shared DLL would be removed. Version control was primarily managed by location, making it a precarious system at best.

Enter .NET Framework: The GAC Revolution

When Microsoft introduced the .NET Framework, it brought a sophisticated solution to these problems: the Global Assembly Cache (GAC). Located at C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\assembly\ (for .NET 4.0 and later), the GAC represented a significant improvement in shared library management.

The most revolutionary aspect was the introduction of assembly identity. Instead of relying solely on filenames and locations, each assembly now had a unique identity consisting of:

- Simple name (e.g., “MyCompany.MyLibrary”)

- Version number (e.g., “1.0.0.0”)

- Culture information

- Public key token

A typical assembly full name would look like this:

MyCompany.MyLibrary, Version=1.0.0.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=b77a5c561934e089

This robust identification system meant that multiple versions of the same assembly could coexist peacefully, solving many of the versioning nightmares that plagued the VB6 era.

The Modern Approach: Private Dependencies

Fast forward to 2025, and we’re living in what I call the “brave new world” of .NET for multi-operative systems. The landscape has changed dramatically. Storage is no longer the premium resource it once was, and the trend has shifted away from shared libraries toward application-local deployment.

Modern applications often ship with their own private version of the .NET runtime and dependencies. This approach eliminates the risks associated with shared components and gives applications complete control over their runtime environment.

Reflection on Technology Evolution

While researching Blazor’s future and seeing discussions about Microsoft’s technology choices, I’m reminded that technology evolution is a constant journey. Organizations move slowly in production environments, and that’s often for good reason. The shift from COM components to GAC to private dependencies wasn’t just a technical evolution – it was a response to real-world problems and changing resources.

This journey from VB6 to modern .NET reveals an interesting pattern: sometimes the best solution isn’t sharing resources but giving each application its own isolated environment. It’s fascinating how the decreasing cost of storage and increasing need for reliability has transformed our approach to dependency management.

As I return to my AI research, this trip down memory lane serves as a reminder that while technology constantly evolves, understanding its history helps us appreciate the solutions we have today and better prepare for the challenges of tomorrow.

by Joche Ojeda | Jan 17, 2025 | DevExpress, dotnet

My mom used to say that fashion is cyclical – whatever you do will eventually come back around. I’ve come to realize the same principle applies to technology. Many technologies have come and gone, only to resurface again in new forms.

Take Command Line Interface (CLI) commands, for example. For years, the industry pushed to move away from CLI towards graphical interfaces, promising a more user-friendly experience. Yet here we are in 2025, witnessing a remarkable return to CLI-based tools, especially in software development.

As a programmer, efficiency is key – particularly when dealing with repetitive tasks. This became evident when my business partner Javier and I decided to create our own application templates for Visual Studio. The process was challenging, mainly because Visual Studio’s template infrastructure isn’t well maintained. Documentation was sparse, and the whole process felt cryptic.

Our first major project was creating a template for Xamarin.Forms (now .NET MAUI), aiming to build a multi-target application template that could work across Android, iOS, and Windows. We relied heavily on James Montemagno’s excellent resources and videos to navigate this complex territory.

The task became significantly easier with the introduction of the new SDK-style projects. Compared to the older MSBuild project types, which were notoriously complex to template, the new format makes creating custom project templates much more straightforward.

In today’s development landscape, most application templates are distributed as NuGet packages, making them easier to share and implement. Interestingly, these packages are primarily designed for CLI use rather than Visual Studio’s graphical interface – a perfect example of technology coming full circle.

Following this trend, DevExpress has developed a new set of application templates that work cross-platform using the CLI. These templates leverage SkiaSharp for UI rendering, enabling true multi-IDE and multi-OS compatibility. While they’re not yet compatible with Apple Silicon, that support is likely coming in future updates.

The templates utilize CLI under the hood to generate new project structures. When you install these templates in Visual Studio Code or Visual Studio, they become available through both the CLI and the graphical interface, offering developers the best of both worlds.

Here is the official DevExpress blog post for the new application templates

https://www.devexpress.com/subscriptions/whats-new/#project-template-gallery-net8

Templates for Visual Studio

DevExpress Template Kit for Visual Studio – Visual Studio Marketplace

Templates for VS Code

DevExpress Template Kit for VS Code – Visual Studio Marketplace

If you want to see the list of the new installed DevExpress templates, you can use the following command on the terminal

dotnet new list dx

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this technological cycle. Which approach do you prefer for creating new projects – CLI or graphical interface? Let me know in the comments below!

by Joche Ojeda | Jan 14, 2025 | C#, dotnet, MetaProgramming, Reflection

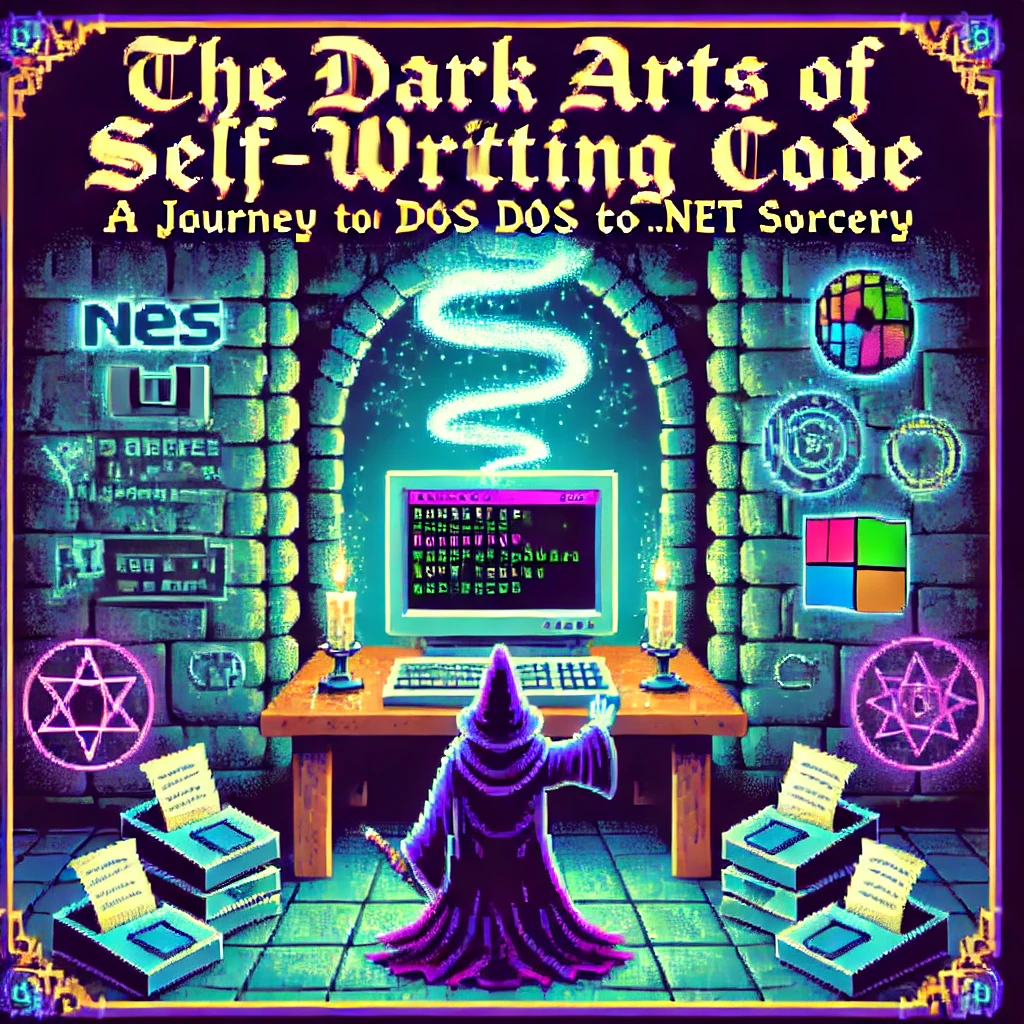

The Beginning of a Digital Sorcerer

Every master of the dark arts has an origin story, and mine begins in the ancient realm of MS-DOS 6.1. What started as simple experimentation with BAT files would eventually lead me down a path to discovering one of programming’s most powerful arts: metaprogramming.

I still remember the day my older brother Oscar introduced me to the mystical DIR command. He was three years ahead of me in school, already initiated into the computer classes that would begin in “tercer ciclo” (7th through 9th grade) in El Salvador. This simple command, capable of revealing the contents of directories, was my first spell in what would become a lifelong pursuit of programming magic.

My childhood hobbies – playing video games, guitar, and piano (a family tradition, given my father’s musical lineage) – faded into the background as I discovered the enchanting world of DOS commands. The discovery that files ending in .exe were executable spells and .com files were commands that accepted parameters opened up a new realm of possibilities.

Armed with EDIT.COM, a primitive but powerful text editor, I began experimenting with every file I could find. The real breakthrough came when I discovered AUTOEXEC.BAT, a mystical scroll that controlled the DOS startup ritual. This was my first encounter with automated script execution, though I didn’t know it at the time.

The Path of Many Languages

My journey through the programming arts led me through many schools of magic: Turbo Pascal, C++, Fox Pro (more of an application framework than a pure language), Delphi, VB6, VBA, VB.NET, and finally, my true calling: C#.

During my university years, I co-founded my first company with my cousin “Carlitos,” supported by my uncle Carlos Melgar, who had been like a father to me. While we had some coding experience, our ambition to create our own ERP system led us to expand our circle. This is where I met Abel, one of two programmers we recruited who were dating my cousins at the time. Abel, coming from a Delphi background, introduced me to a concept that would change my understanding of programming forever: reflection.

Understanding the Dark Arts of Metaprogramming

What Abel revealed to me that day was just the beginning of my journey into metaprogramming, a form of magic that allows code to examine and modify itself at runtime. In the .NET realm, this sorcery primarily manifests through reflection, a power that would have seemed impossible in my DOS days.

Let me share with you the secrets I’ve learned along this path:

The Power of Reflection: Your First Spell

// A basic spell of introspection

Type stringType = typeof(string);

MethodInfo[] methods = stringType.GetMethods();

foreach (var method in methods)

{

Console.WriteLine($"Discovered spell: {method.Name}");

}

This simple incantation allows your code to examine itself, revealing the methods hidden within any type. But this is just the beginning.

Conjuring Objects from the Void

As your powers grow, you’ll learn to create objects dynamically:

public class ObjectConjurer

{

public T SummonAndEnchant<T>(Dictionary<string, object> properties) where T : new()

{

T instance = new T();

Type type = typeof(T);

foreach (var property in properties)

{

PropertyInfo prop = type.GetProperty(property.Key);

if (prop != null && prop.CanWrite)

{

prop.SetValue(instance, property.Value);

}

}

return instance;

}

}

Advanced Rituals: Expression Trees

Expression<Func<int, bool>> ageCheck = age => age >= 18;

var parameter = Expression.Parameter(typeof(int), "age");

var constant = Expression.Constant(18, typeof(int));

var comparison = Expression.GreaterThanOrEqual(parameter, constant);

var lambda = Expression.Lambda<Func<int, bool>>(comparison, parameter);

The Price of Power: Security and Performance

Like any powerful magic, these arts come with risks and costs. Through my journey, I learned the importance of protective wards:

Guarding Against Dark Forces

// A protective ward for your reflective operations

[SecurityPermission(SecurityAction.Demand, ControlEvidence = true)]

public class SecretKeeper

{

private readonly string _arcaneSecret = "xyz";

public string RevealSecret(string authToken)

{

if (ValidateToken(authToken))

return _arcaneSecret;

throw new ForbiddenMagicException("Unauthorized attempt to access secrets");

}

}

The Cost of Power

| Ritual Type |

Energy Cost (ms) |

Mana Usage |

| Direct Cast |

1 |

Baseline |

| Reflection |

10-20 |

2x-3x |

| Cached Cast |

2-3 |

1.5x |

| Compiled |

1.2-1.5 |

1.2x |

To mitigate these costs, I learned to cache my spells:

public class SpellCache

{

private static readonly ConcurrentDictionary<string, MethodInfo> SpellBook

= new ConcurrentDictionary<string, MethodInfo>();

public static MethodInfo GetSpell(Type type, string spellName)

{

string key = $"{type.FullName}.{spellName}";

return SpellBook.GetOrAdd(key, _ => type.GetMethod(spellName));

}

}

Practical Applications in the Modern Age

Today, these dark arts power many of our most powerful frameworks:

- Entity Framework uses reflection for its magical object-relational mapping

- Dependency Injection containers use it to automatically wire up our applications

- Serialization libraries use it to transform objects into different forms

- Unit testing frameworks use it to create test doubles and verify behavior

Wisdom for the Aspiring Sorcerer

From my journey from DOS batch files to the heights of .NET metaprogramming, I’ve gathered these pieces of wisdom:

- Cache your incantations whenever possible

- Guard your secrets with proper wards

- Measure the cost of your rituals

- Use direct casting when available

- Document your dark arts thoroughly

Conclusion

Looking back at my journey from those first DOS commands to mastering the dark arts of metaprogramming, I’m reminded that every programmer’s path is unique. That young boy who first typed DIR in MS-DOS could never have imagined where that path would lead. Today, as I work with advanced concepts like reflection and metaprogramming in .NET, I’m reminded that our field is one of continuous learning and evolution.

The dark arts of metaprogramming may be powerful, but like any tool, their true value lies in knowing when and how to use them effectively. Remember, while the ability to make code write itself might seem like sorcery, the real magic lies in understanding the fundamentals and growing from them. Whether you’re starting with basic commands like I did or diving straight into advanced concepts, every step of the journey contributes to your growth as a developer.

And who knows? Maybe one day you’ll find yourself teaching these dark arts to the next generation of digital sorcerers.

by Joche Ojeda | Jan 13, 2025 | Uncategorized

As the new year (2025) starts, I want to share some insights from my role at Xari. While Javier and I founded the company together (he’s the Chief in Command, and I’ve dubbed myself the Minister of Dark Magic), our rapid growth has made these playful titles more meaningful than we expected.

Among my self-imposed responsibilities are:

- Providing ancient knowledge to the team (I’ve been coding since MS-DOS 6.1 – you do the math!)

- Testing emerging technologies

- Deciphering how and why our systems work

- Achieving the “impossible” (even if impractical, we love proving it can be done)

Our Technical Landscape

As a .NET shop, we develop everything from LOB applications to AI-powered object detection systems and mainframe database connectors. Our preference for C# isn’t just about the language – it’s about the power of the .NET ecosystem itself.

.NET’s architecture, with its intermediate language and JIT compilation, opens up fascinating possibilities for code manipulation. This brings us to one of my favorite features: Reflection, or more broadly, metaprogramming.

Enter Harmony: The Art of Runtime Magic

Harmony is a powerful library that transforms how we approach runtime method patching in .NET applications. Think of it as a sophisticated Swiss Army knife for metaprogramming. But why would you need it?

Real-World Applications

1. Performance Monitoring

[HarmonyPatch(typeof(CriticalService), "ProcessData")]

class PerformancePatch

{

static void Prefix(out Stopwatch __state)

{

__state = Stopwatch.StartNew();

}

static void Postfix(Stopwatch __state)

{

Console.WriteLine($"Processing took {__state.ElapsedMilliseconds}ms");

}

}

2. Feature Toggling in Legacy Systems

[HarmonyPatch(typeof(LegacySystem), "SaveToDatabase")]

class ModernizationPatch

{

static bool Prefix(object data)

{

if (FeatureFlags.UseNewStorage)

{

ModernDbContext.Save(data);

return false; // Skip old implementation

}

return true;

}

}

The Three Pillars of Harmony

Harmony offers three powerful ways to modify code:

1. Prefix Patches

- Execute before the original method

- Perfect for validation

- Can prevent original method execution

- Modify input parameters

2. Postfix Patches

- Run after the original method

- Ideal for logging

- Can modify return values

- Access to execution state

3. Transpilers

- Modify the IL code directly

- Most powerful but complex

- Direct instruction manipulation

- Used for advanced scenarios

Practical Example: Method Timing

Here’s a real-world example we use at Xari for performance monitoring:

[HarmonyPatch(typeof(Controller), "ProcessRequest")]

class MonitoringPatch

{

static void Prefix(out Stopwatch __state)

{

__state = Stopwatch.StartNew();

}

static void Postfix(MethodBase __originalMethod, Stopwatch __state)

{

__state.Stop();

Logger.Log($"{__originalMethod.Name} execution: {__state.ElapsedMilliseconds}ms");

}

}

When to Use Harmony

Harmony shines when you need to:

- Modify third-party code without source access

- Implement system-wide logging or monitoring

- Create modding frameworks

- Add features to sealed classes

- Test legacy systems

The Dark Side of Power

While Harmony is powerful, use it wisely:

- Avoid in production-critical systems where stability is paramount

- Consider simpler alternatives first

- Be cautious with high-performance scenarios

- Document your patches thoroughly

Conclusion

In our work at Xari, Harmony has proven invaluable for solving seemingly impossible problems. While it might seem like “dark magic,” it’s really about understanding and leveraging the powerful features of .NET’s architecture.

Remember: with great power comes great responsibility. Use Harmony when it makes sense, but always consider simpler alternatives first. Happy coding!